Top scorer

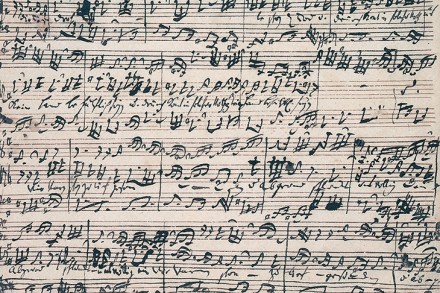

Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess springs to life fully formed, and pulls you in before a word has been sung. A whirlwind flourish; the hectic bustle of violins and xylophone, and then a quick fade into an image of a woman cradling a child and ‘Summertime’, the very first number we hear sung. The aria’s fame