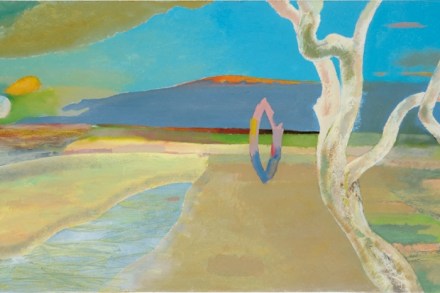

We must never again let this 19th century Norwegian master slip into oblivion

You won’t have heard of Peder Balke. Yet this long-neglected painter from 19th-century Norway is now the subject of a solo show at the National Gallery. And it’s an absolute revelation. Walking around, I marvelled at the intensity of a man obsessed with revealing the frozen grandeur and elemental drama dominating his country’s northernmost shores. Like Turner, he was driven by a restless urge to travel, discovering landscapes that enlarged and transformed his vision of the world. In 1832 he took an arduous sea journey to the far north of Norway, ceaselessly sketching the rugged coast and mountains along the way. His excitement grew as he passed the primal North