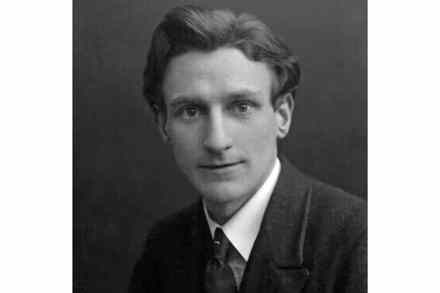

The psychopath who wrecked New York

Robert Moses was the man, they say, who built New York. He was never elected to anything, yet he had absolute control of all public works in the city for more than 40 years, until 1968. His record was mind-bending. He personally conceived and directed the building of 627 miles of New York parkways and expressways, seven of New York’s bridges, the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel and the entire Long Island highway system; he built the Lincoln Centre arts complex, the United Nations, Jones Beach Park, JFK airport, Central Park zoo and the Shea Stadium; he built 658 playgrounds, 11 swimming pools, 673 baseball pitches and cleared thousands of acres of slums;