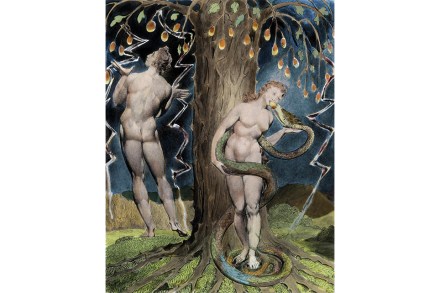

The subversive message of Paradise Lost

For those of us who have long loved (or hated) Paradise Lost, this is one of those rare and refreshing books that invites us to compare our feelings with other committed readers over the centuries. The poemmay well be the only major work in the western canon that nobody can avoid for long – even if it comes down to making a decision not to read it at all, or just to give up trying. Orlando Reade argues that it may also be the most ‘revolutionary’ text commonly available in modern classrooms – written by a man who, in his time, took extreme positions on everything from divorce (he was