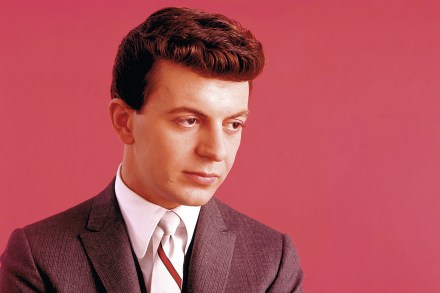

Meet Dion, one of the last living links to the earliest days of rock ’n’ roll

Only two of the Beatles’ pop contemporaries are depicted on the cover of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. One is Bob Dylan. The other is Dion DiMucci. In a pleasing third-act twist, Dylan contributes the liner notes to Dion’s new album Blues With Friends — an act of deference that the recipient is still processing. ‘I asked him, I didn’t know if he had the time, but he sent me back those paragraphs and said that I knew how to write a song.’ He whistles. ‘That’s from a Nobel Prize winner. I thought, I’ll take it, I’ll take it!’ So he should. Dion — like Kylie, a single moniker