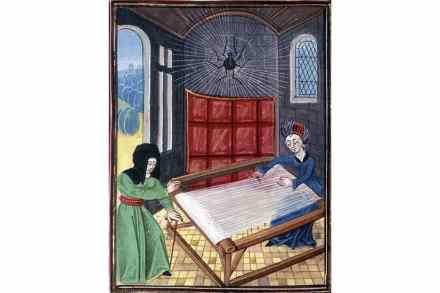

It’s time to buy a British jumper

When did you last bump into the words ‘Made in Britain’ on a jumper, shirt or pair of trousers? There’s a chance, if you’re under 40, that you’ve never actually seen those words printed in an item of clothing – ever. And that’s quite a problem, particularly when you consider that we find ourselves in an era when the Prime Minister’s favourite two words are ‘national resilience’. The simple fact is that when it comes to clothes we aren’t resilient. In fact quite the reverse: in the past year Britain imported something like £15 billion-worth of textiles and clothing (compared with clothing exports of around £3 billion). So in addition