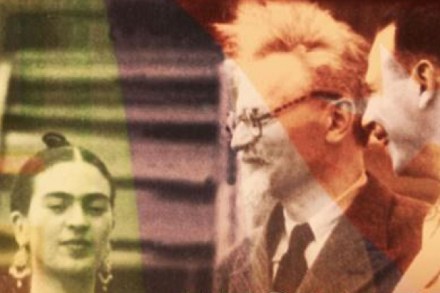

Both lyricist and agitator: the split personality of Vladimir Mayakovsky

Why increase the number of suicides? Better to increase the output of ink! wrote Vladimir Mayakovsky in 1926 in response to the death of a fellow poet. Four years later, aged 36, he shot himself. What drove the successful author, popular with the public and recognised by officialdom, to suicide? Bengt Jangfeldt provides some clues to this question in his detailed, source-rich biography. Mayakovsky came to poetry as a Futurist, co-authoring the 1912 manifesto A Slap in the Face of Public Taste, which granted poets the right ‘to feel an insurmountable hatred for the language existing before their time’. That the new era demanded a new language was a principle