Life among the world’s biggest risk-takers

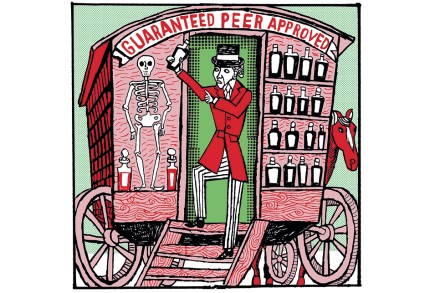

The Italian actuary Bruno de Finetti, writing in 1931, was explicit: ‘Probability does not exist.’ Probability, it’s true, is simply the measure of an observer’s uncertainty; and in The Art of Uncertainty, the British statistician David Spiegelhalter explains how this extraordinary and much-derided science has evolved to the point where it is even able to say useful things about why matters have turned out the way they have, based purely on present evidence. Spiegelhalter was a member of the Statistical Expert Group of the 2018 UK Infected Blood Inquiry, and you know his book’s a winner the moment he tells you that between 650 and 3,320 people nationwide died from