What does Belarus’s opposition leader want?

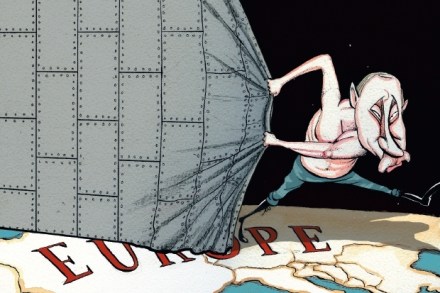

There is an assumption that those fighting tyranny must instead want Western-style democracy, that the arc of history bends towards liberal representative government, allied inevitably to Washington and Brussels. Many former Soviet Union countries saw their politburos overthrown by young middle-class people espousing the desire for this kind of politics — from the Rose Revolution in Georgia to the Orange Revolution and Euromaiden protests in Ukraine (whether or not they eventually received that form of government is a different matter). But there is no logical imperative that connects dissatisfaction towards an autocrat with the kind of government and geopolitical order that will replace him, whether in Eastern Europe or elsewhere. Belarus,