Afterthoughts

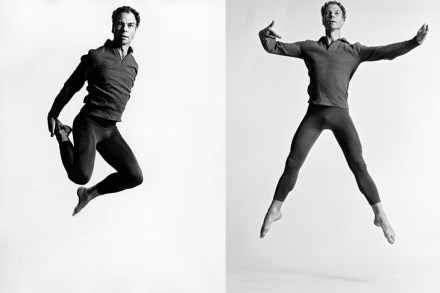

The blackness that sweeps along the stage behind Sylvie Guillem’s disappearing figure in the Russell Maliphant piece on her farewell tour is an astonishing moment. One flinches. An eclipse has happened and the light has just run away with her. All gone. Michael Hulls’s momentous lighting states Guillem’s intentions as clearly as Elias Benxon’s filmwork in the closing piece, Mats Ek’s Bye, which shows this singular performer quitting her elite world of imagemaking and humbly, nervously, going out to join the masses in the street. After lights out, she intends there to be no legacy. As I had hoped might happen, elements of Guillem’s closing show, unveiled at Sadler’s Wells