Swaggerific display of pumping chests and crotch-grabbing struts: NYDC’s Speak Volumes reviewed

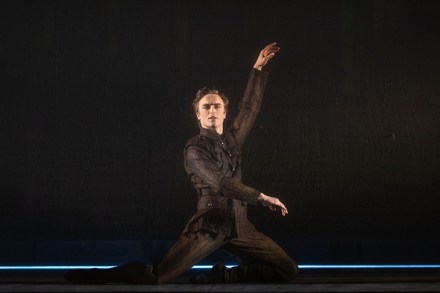

Last week I attended a dance performance in person for the first time since March last year. If you’d asked me to choose the ideal show for the occasion, I’d have probably picked something with marquee names and lavish costumes — a classical ballet gala, or maybe one of Matthew Bourne’s glittering productions. As it happens, I watched teenagers in bomber jackets snarl at each other in between dance-offs — and actually, it was just the ticket. Mental health issues among teens have rocketed during the pandemic, and this crew, from National Youth Dance Company, drive the point home with a hard-nosed production that doesn’t ask so much as command