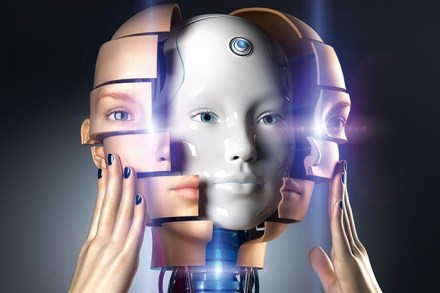

Will the photo of your lost loved one be replaced by a chatty robot?

They didn’t call Diogenes ‘the Cynic’ for nothing. He lived to shock the (ancient Greek) world. When I’m dead, he said, just toss my body over the city walls to feed the dogs. The bit of me that I call ‘I’ won’t be around to care. The revulsion we feel at this idea tells us something important: that the dead can be wronged. Diogenes may not have cared what happened to his corpse, but we do; and doing right by the dead is a job of work. Some corpses are reduced to ash, some are buried, and some are fed to vultures. In each case, the survivors all feel, rightly,