The new religion of the Church of England

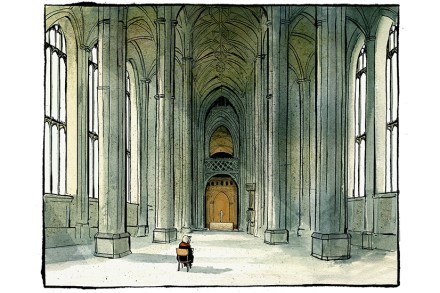

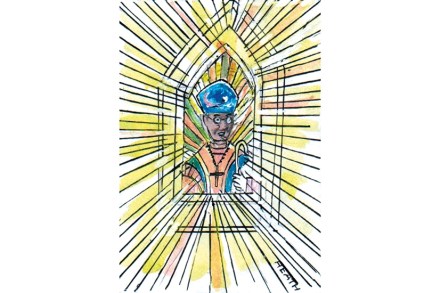

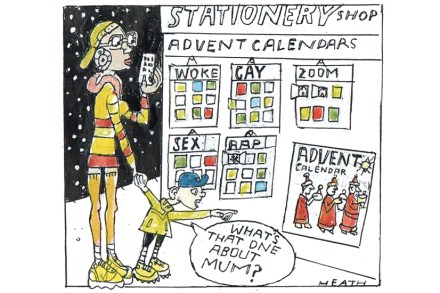

With a heavy heart I must return once more to the subject of the Church of England. I recognise that is not a subject for everybody, and occasionally someone implies that it should not be a subject for me. But I am concerned about the fate of the national church because as the new religion heaves ever clearer into view, I realise that I prefer the old religion to the new one. I would rather attempts to influence the country’s morals were preached from a pulpit than through group stampede on Twitter. And though we haven’t heard much from actual pulpits for more than a year, the church hierarchy has