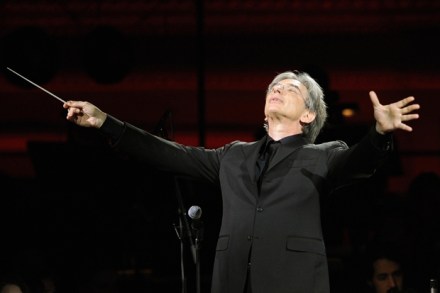

The rude, ripe tastelessness of John Eliot Gardiner’s Berlioz is the perfect antidote to Haitink’s Instagram Bruckner

Conducting is one of those professions — being monarch is perhaps another — where the less you do, the more everyone loves you. Orchestral players, for example, tend not to complain about being let off early from rehearsals. I prefer my maestros to have their head under the bonnet: loosening, tightening, fixing, replacing. Much of the classical music world, however, fetishises the idea of ‘letting the music speak for itself’. As if ‘the music’ were an objective thing. As if the score were a rendering that could be printed out in 3D, rather than a map to be deciphered and interpreted. This goes some way, I think, to explain the