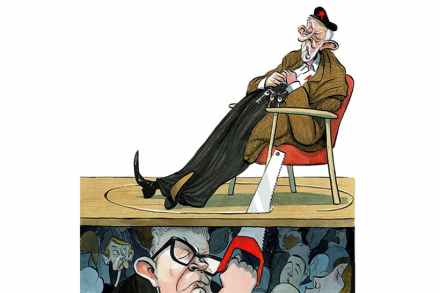

Trump should take lessons in lying from Joe Biden

Gstaad It snowed on the last two days of August up here, and why not? We’ve traded freedom of speech for freedom from speech, so on an upside-down planet, snow in the Alps in August is the new normal. The world is suddenly a grim place, a sick prank when you think about it. It’s a kamikaze fantasy with the bad guys winning and being cheered on by the left and the media. The virus is now a metaphor, religion having been cast aside by the global elite who follow only their interests and think of the rest of us as cannon fodder. Reading the papers a couple of weeks