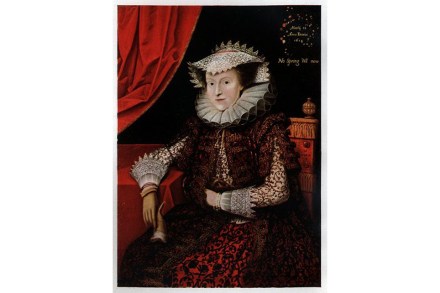

Four female writers at the court of Elizabeth I

Almost a century ago, in A Room of One’s Own, Virginia Woolf claimed that if William Shakespeare had had an equally talented sister the obstacles to her sharing his vocation would have been insurmountable. Woolf’s argument that a woman needs ‘money and a room of her own’ in order to write proved persuasive. ‘Shakespeare’s sister’ has become a pop-cultural trope. So perhaps it’s unsurprising that the distinguished American scholar of the Renaissance Ramie Targoff should borrow the phrase for a study of four woman writers. Her title offers a shortcut to understanding how significant this immensely accomplished quartet is for readers and writers today. Not that Targoff’s elegantly readable, immaculately