A poem a day

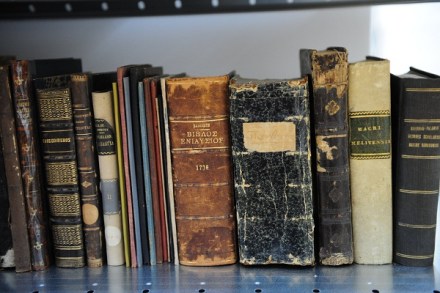

I’m fresh back from the Port Eliot festival in Cornwall where I spent a day prescribing poetry prescriptions to those in need. It was a revelatory experience. Having spent twenty years or so promoting poetic excellence through the Forward Prizes for Poetry and broader access to the art-form through National Poetry Day, I’ve been battling with the challenge of making poetry appear more relevant to people in their everyday lives. Battling because there is no doubt that most people find poetry intimidating. It’s a fusty, dusty, back of a bookshop, elite, slim-volumed thing that’s not really for them. The occasional line of a poem will be lodged in their mind