Jonathan Aitken’s diary: My life as a Christian outreach speaker

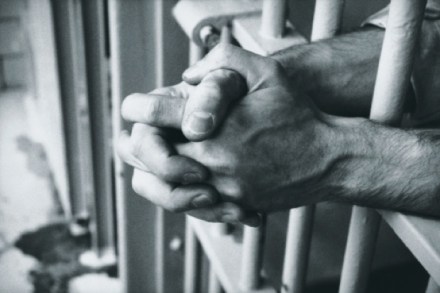

The last time I wrote for The Spectator I was sitting in a prison cell. I sent the then editor a poem called ‘The Ballad of Belmarsh Gaol’. Instead of printing it in the poetry column, Frank Johnson put it on the magazine’s cover. It received what is euphemistically called ‘a mixed reception’ — so mixed that I have never again tried my hand at verse. In those dark days 14 years ago I was wrestling with my self-inflicted agonies of defeat, disgrace, divorce, bankruptcy and jail. As I contemplated my non-future, its only certainty was that I would never again be in demand as a public speaker or as a