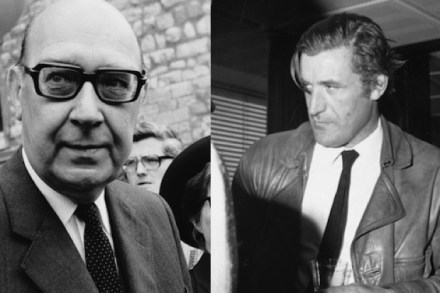

Ted Hughes vs Philip Larkin – whose team are you on?

Are you a Phillist or a Teddist? A Phillist is not a Philistine in a hurry, but one who warms to the sensibility of Philip Larkin. A Teddist prefers that of Ted Hughes. Recent BBC documentaries on each poet have clarified the choice. Whose vision of life is more convincing and compelling – the glum librarian or the dashing naturalist who made the ladies swoon (in and out of ovens)? To define their difference it’s tempting to call Hughes a Romantic, and Larkin an anti-Romantic. But it doesn’t quite work. Hughes’s fascinated reverence for the natural world has some Romantic features, but his vision of nature’s brutality is hardly ‘Daffodils’.