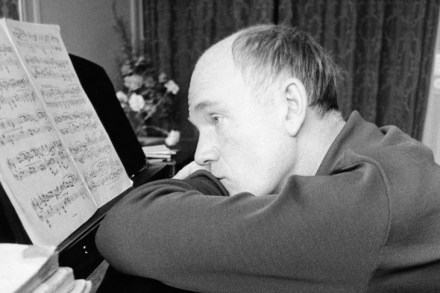

Why did the Soviets not want us to know about the pianist Maria Grinberg?

Only four women pianists have recorded complete cycles of the Beethoven piano sonatas: Maria Grinberg, Annie Fischer, H. J. Lim and Mari Kodama. I’ve written before about the chain-smoking ‘Ashtray Annie’ Fischer: she was a true poet of the piano and her Beethoven sonatas are remarkably penetrating — as, alas, is the sound of her beaten-up Bösendorfer. Lim produced her cycle in a hurry when she was just 24; it’s engaging but breathless. Kodama’s set, just completed, is a bit polite. Which leaves Maria Grinberg (1908–78), whose recordings remain just where the Soviet authorities wanted them. In obscurity. That is shameful — and not because she was the first woman