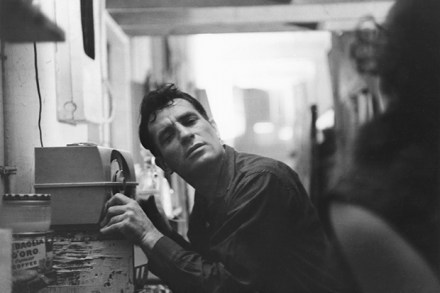

Beat echoes

Laid out flat, running the length of the exhibition, the original scroll of Jack Kerouac’s On the Road forms the spine of the large Beat Generation show at the Pompidou Centre in Paris. Even for those familiar with the published version of the manuscript seeing this holy relic — the founding document for all sects of Beat worshippers — is a powerful experience. For about a minute. It’s everything else — the movies, the posters, the paraphernalia — that takes the time and generates an exhibition on such a tremendous scale. But how could it not sprawl? You start with the writers — Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg and William Burroughs —