When did postmodernism begin?

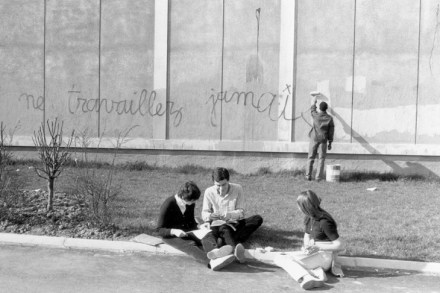

There’s a scene in Martin Amis’s 1990s revenge comedy The Information in which a book reviewer, who’s crushed by his failures and rendered literally impotent by his best friend’s success, is sitting in a low-lit suburban room beside a girl (not his wife) named Belladonna: ‘She was definitely younger than him. He was a modernist. She was the thing that came next.’ Stuart Jeffries argues in his new book that the thing that came next was in fact a thing that started a couple of decades before Amis wrote The Information. In Jeffries’s telling, postmodernity can be dated to 13 August 1971, when Richard Nixon held a closed-door meeting that