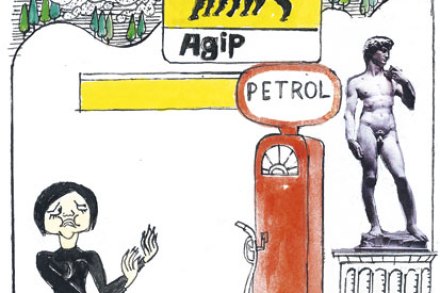

Moving statues

One of the stranger disputes of the past few weeks has concerned a Victorian figure that has occupied a niche in the centre of Oxford for more than a century without, for the most part, attracting any attention at all. Now, of course, the Rhodes Must Fall campaign is demanding that the sculpture — its subject having been posthumously found guilty of racism and imperialism — should be taken down from the façade of Oriel College. The controversy is a reminder of the fact, sometimes forgotten by the British, that public statues are intensely political. This was clear — until quite recently, at least — when one drove into the