Eric Zemmour’s big weakness has been exposed

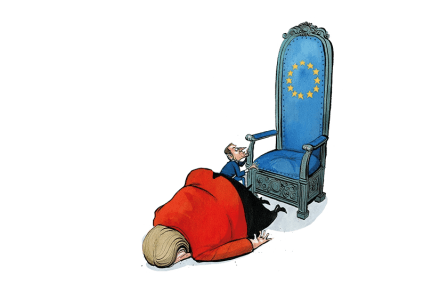

George W Bush will forever be in debt to The Donald. Before Trump became the 45th president of the United States, the man nicknamed ‘Dubya’ was widely considered by many Americans to be the most inept. Then came Trump. No longer was Bush a clown. The American left forget how they’d demonised him and looked wistfully to a time when there was dignity in the Oval Office. Marine Le Pen is experiencing something similar since Eric Zemmour’s emergence as a presidential candidate. She is no longer Public Enemy No. 1 since her detractors turned their fire on Zemmour; where once their battle-cry before any election was ‘Anyone but Le Pen’, now