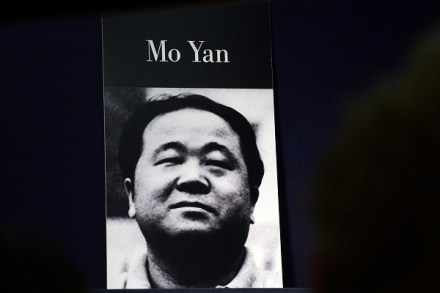

Mo Yan's malignant apology for 'necessary' censorship

The Chinese writer Mo Yan collected the Nobel Prize for Literature last night. In his acceptance lecture, he reiterated his view that a degree of censorship is ‘necessary’ in the world, and compared it to airport security. The comparison is utterly base. Airport security is a fleeting restriction on personal liberty; a social contract entered into freely by making the decision to travel by air. Censorship is a legal mechanism imposed on entire societies by a self-appointed oligarchy that maintains itself by persecuting and prosecuting individual transgressors. Mo Yan’s logic is as flawed as his apology is malignant. Having said that, his enthusiasm for censorship was quite restrained on this occasion: he told Granta recently that