Taki: My main gripe with Gaddafi is the quality of his cocaine

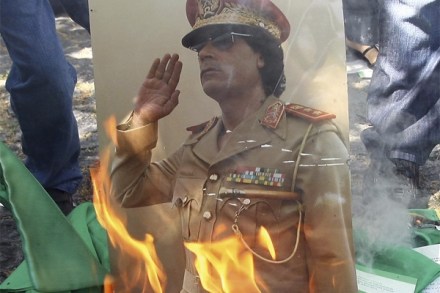

New York Libyans are among the most civilised people on earth. When a Russian hooker (I assume) killed a Libyan Air Force officer, a mob stormed the Russian embassy seeking revenge. They failed, but not for lack of trying. This time last year, another mob murdered the American ambassador and three others in a similar attack, although no Yankee gal had harmed any Libyan flier. The civilised Libyans also did democracy proud when they captured Gaddafi. They shot him up the bum with an AK47, dispensing with a boring trial. The bad guy that got away is Hannibal Gaddafi, who with wifey used to beat up and torture Filipino servants