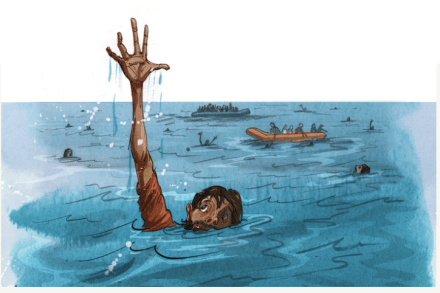

The Syrians who can’t go home

In a waiting room in Beirut’s Adlieh district, with harsh fluorescent lighting glaring down on us, the handcuffed prisoners, we took turns to rotate between the floor and the splintered wood of a short bench. On the wall, someone had scrawled a life-sized drawing of an AK-47, its muzzle inscribed with the words ‘Pew! Pew!’ Royal blue fingerprints, remnants of the admission process, smudged the plasterboard. Names and dates were scratched into the walls, a record of how long people had been held – days, weeks or months. This was my introduction to Lebanon’s detention centres. In August, I was bundled into the back of a pickup while working with a charity supporting Syrian