The end of days: It Lasts Forever And Then It’s Over, by Anne de Marcken, reviewed

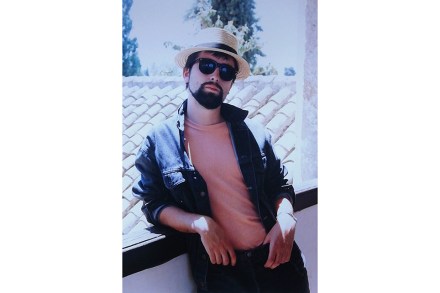

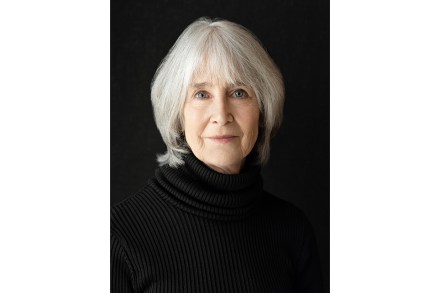

How do you picture the end of days? ‘When I was alive, I imagined something redemptive about the end of the world,’ muses the unnamed narrator in It Lasts Forever And Then It’s Over. ‘I thought it would be a kind of purification. Or at least a simplification. Rectification through reduction.’ But no: ‘The end of the world looks exactly the way you remember. Don’t try to picture the apocalypse. Everything is the same,’ she continues from her vantage point in an afterlife, brought into vivid existence by Anne de Marcken. It’s telling that the author’s biography states that she ‘lives in the United States on unceded land of the