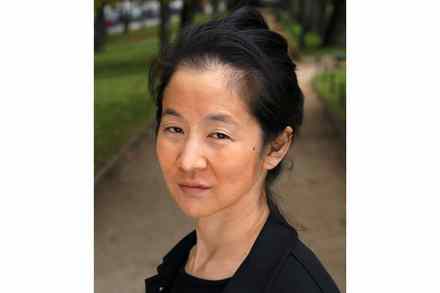

The parent snatchers: The School for Good Mothers, by Jessamine Chan, reviewed

Frida Liu, the 39-year-old mother of a toddler named Harriet, has a very bad day which will haunt her for the length of this novel. She is divorced from Harriet’s father, a middle-aged man called Gust who has left her for a 28-year-old Pilates instructor called Susanna. Harriet will only fall asleep, Frida explains, ‘if I’m holding her hand’. As a consequence, Frida herself has been averaging two hours sleep a night when she finally cracks and decides to leave her daughter unattended so that she can collect some papers from her work place. After her neighbours hear the child crying they call the police and Harriet goes to live