Two sinister siblings: The Mountain Lion, by Jean Stafford, reviewed

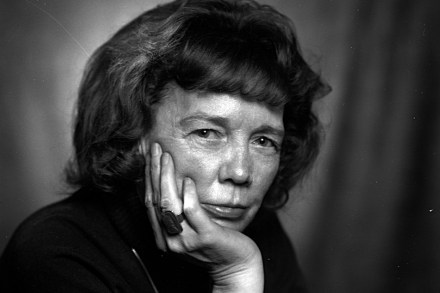

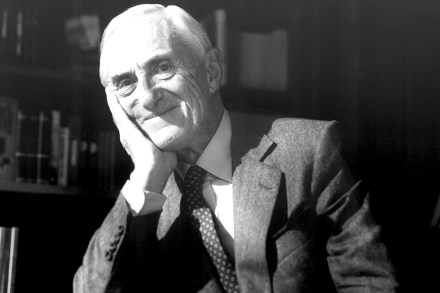

Many of the best literary children – think the creations of Henry James or Elizabeth Bowen – have something creepy about them. These are girls and boys who see through the hypocrisy of adults, and there’s going to be something unnerving about their precocity. Jean Stafford’s Mollie and Ralph took their place in a lineage with James’s Flora and Miles and Bowen’s Henrietta and Leopold when she flung them, bespectacled and prone to nosebleeds, into the world in 1946. Stafford was the first wife of Robert Lowell, and it’s the main thing most people know about her now – unsurprisingly. Lowell was a man who made his mark on his