The world’s first robot artist discusses beauty, Yoko Ono and the perils of AI

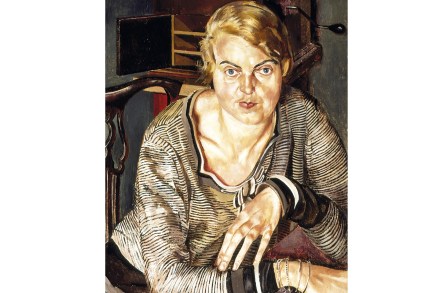

Like a slippery politician on the Today programme, the world’s first robot artist answers the questions she wants rather than the ones she’s been asked. I never had this trouble with Tracey Emin or Maggi Hambling. As we stand before a display of her paintings at London’s Design Museum, I ask Ai-Da whether she thinks her self-portraits are beautiful. What I want to get at, you see, is that, while it’s quite possible for a machine to make something beautiful, it’s hardly comprehensible for a thing made from metal, algorithms and circuitry to appreciate that beauty. ‘I want to see art as a means for us to become more aware