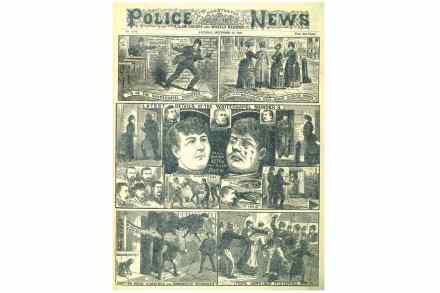

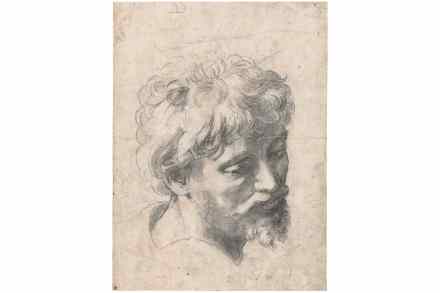

From Leonardo to Hepworth: the art of surgery

A doctor with wild grey hair and mutton chops holds a scalpel in his bloodied hand. He has paused for a moment, allowing one of his students to take his place and complete the incision. It’s a remarkably clean cut; the young man with the clamp has barely dirtied his shirt cuffs. Even so, the patient’s mother, if that’s who she is, weeps in the corner. She can see nothing but frock coats and a segment of open flesh. The 19th-century Philadelphia-based artist Thomas Eakins did not paint surgery as it was, exactly, but he did capture something of its veiled sterility. There may be no gowns or masks in