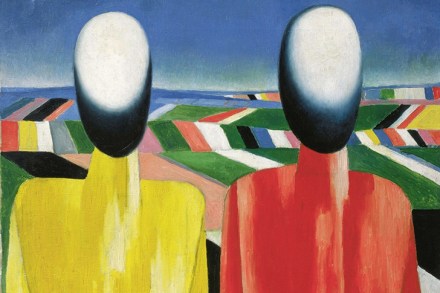

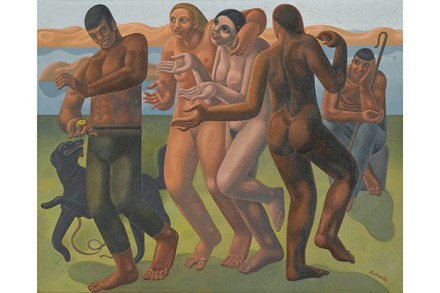

American psyche

The latest exhibition at the Royal Academy is entitled America after the Fall. It deals with painting in the United States during the 1930s: that is, the decade before the tidal surge of abstract expressionism. So this show is a sort of prequel to the RA’s great ab ex blockbuster of last autumn. It might have been called, ‘Before Jackson Began Dripping’. Not much in this selection, though, can compare to the power of the abstract expressionists at their peak in the Forties and Fifties — not even an early work by Pollock himself. But it does include a couple of masterpieces by Edward Hopper, plus several pictures so brashly