Do civil servants need to be ‘robust’ or ‘resilient’?

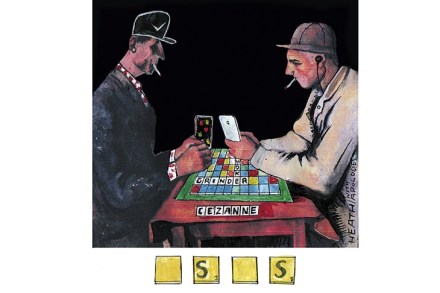

‘Why do they keep saying they need Brazilians?’ asked my husband, coming up for air from a hazy mixture of Radio 4 and whisky. ‘No, darling,’ I tried to explain, ‘not Brazilians. Resilience.’ They had been talking about civil servants sworn at by politicians, or at least being in the same room as swearing. Resilience seems the counterpart to robustness. Sir Alex Allan (who resigned after his report into the conduct of Priti Patel was not taken up wholeheartedly by Boris Johnson) had said that ‘senior civil servants should be expected to handle robust criticism but should not have to face behaviour that goes beyond that’. My mind went to