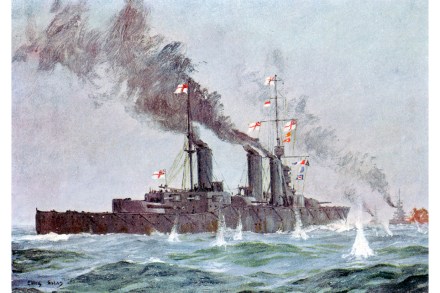

When Britannia ceased to rule the waves

When the Royal Navy celebrated Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee in 1897, 173 ships and 50,000 sailors filled the Solent. The Spectator (3 July 1897) described the ‘endless succession of battleships, cruisers, destroyers, gunboats and torpedo boats’ as offering ‘the most magnificent naval spectacle ever beheld’. More importantly, the fleet at Spithead ‘would have been able to beat any navy or combination of navies that might be brought against it’. It constituted, the magazine proclaimed, a purely defensive weapon, designed only to safeguard the shores of the British Isles, protect the colonies and police the seas ‘for the benefit, not of Englishmen alone, but of the whole world’. Not everyone was