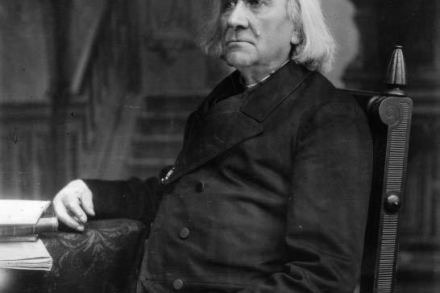

Hit Liszt

Damian Thompson highlights the gems among the prolific and pilloried composer’s nine million notes The extraordinary thing about Franz Liszt is that he remains one of the most famous composers of the 19th century despite the fact that the overwhelming majority of his music is forgotten — and likely to stay forgotten. He wrote enough of it, that’s for sure. If you were to listen to his works one after another without interruption, it would take about a week. I’m basing that estimate on the fact that Leslie Howard’s 98 CDs of Liszt’s complete piano music, which are just about to be reissued by Hyperion, last for just over five