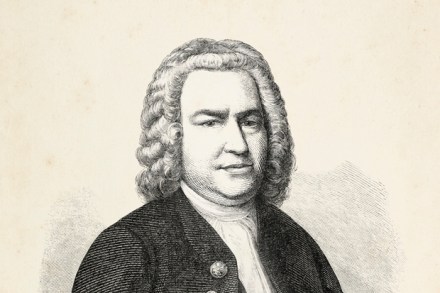

Bach to basics

The churning, rheumatic mechanism of a harpsichord — notes needling your ears like drops of acid rain — doesn’t necessarily play well to an audience whose sensibilities have been moulded around the picture-perfect delicacies of the classical piano. J.S. Bach’s freakishly popular Goldberg Variations remains best known through the recording made by the oddball Canadian pianist Glenn Gould in 1955, a record that would bleed unexpectedly into mainstream consciousness. For a whole generation, the sound of the Goldbergs became interchangeable with Gould’s quicksilver fingers — and a collective amnesia grew around the fact that Bach had actually conceived his most famous keyboard work for the harpsichord. Six decades on, a