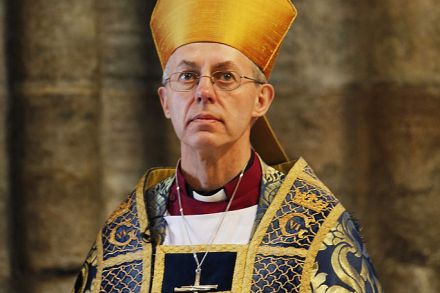

The tin ear of Justin Welby

29 min listen

The former Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby, is back in the news following his interview this week with the BBC’s Laura Kuenssberg. The interview – his first since he resigned last November – was clearly Welby’s attempt to draw a line under the abuse scandal that cost him his job. The 2024 Makin report concluded that the Church of England missed many opportunities to investigate the late John Smyth, one of the most prolific abusers associated with the Anglican Church. However, the biggest headline from the interview was that Welby would ‘forgive’ John Smyth were he alive today. Albeit unintentionally, the former Archbishop of Canterbury ended up cementing his reputation