John Stott: the centenary of a true radical

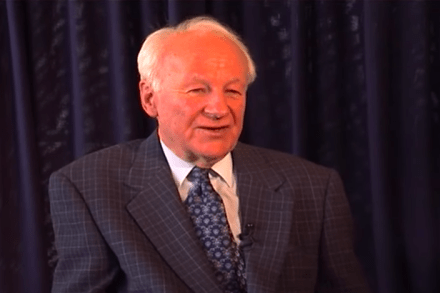

Much has been made of the Queen’s Christian faith in the aftermath of the death of her husband the Duke of Edinburgh. For decades, John Stott, who served as the Queen’s chaplain, shepherded Her Majesty in that faith. Yet although his preaching brought him into contact with Royalty, led to him selling millions of books and even earned him a place among Time magazine’s 100 most influential people in the world, Stott – born a century ago this week – remained a humble man. Stott lived in spartan simplicity in a two-room flat above a garage. Author of more than 50 internationally best-selling books, he assigned all his royalties to a