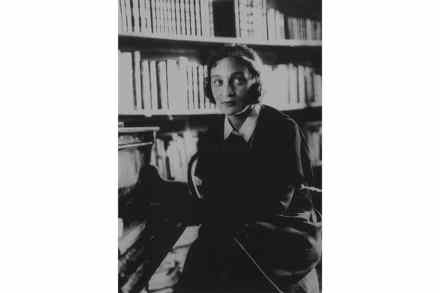

Playing until her fingers bled: the dedication of the pianist Maria Yudina

The 20th century was an amazing time for Russian pianists, and the worse things got, politically and militarily, the more great pianists thrived, despite the extreme danger and discomfort in which they lived and in which some of them died. If we think immediately of Richter, the greatest of them all, and Gilels, there are at least 20 more that we could add without exaggeration. One of the most important was without question Maria Yudina, born in 1899, who astonishingly survived until 1970. She was not just a sovereign artist but an eccentric of the kind and degree that only Russia seems able and willing to supply. Reading a biography