Picture books for grown-ups

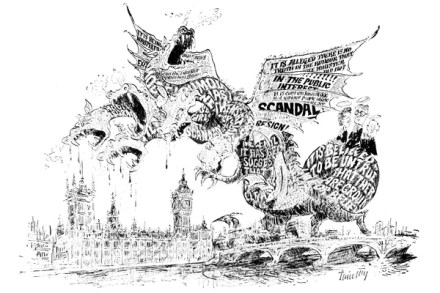

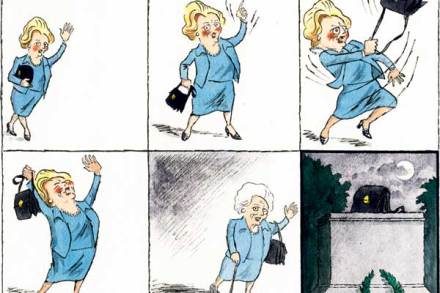

Art Spiegelman, the American cartoonist behind Maus, the celebrated Holocaust cartoon, dreamt up a good definition of graphic novels: comics you need a bookmark for. This jolly show about the British graphic novel takes an even broader approach. It begins with Hogarth’s 1731 series, ‘A Harlot’s Progress’, the tale of an ingénue in London who becomes a prostitute and dies of syphilis. You’d need an awfully big bookmark for the six original paintings in Hogarth’s series. But the point is well made — the idea of telling stories through a series of pictures has been around for a long time in Britain. Perhaps that’s why we’ve often denigrated cartoons and