The fount of all knowledge

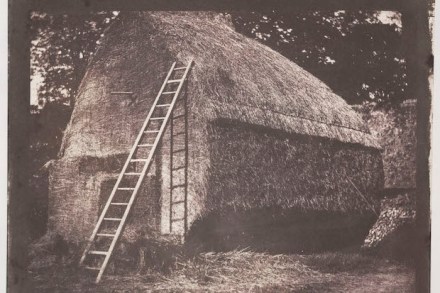

Somewhere around the middle of the 17th century our modern concept of the museum began to take shape. Until then the cabinet of curiosities formed by a prince or a dilettante was on show solely to his friends or to scholars deemed worthy of having it unlocked. Nothing in the way of a systematic catalogue existed to help them navigate the gallimaufry of odd objects filling its shelves and cupboards. A Japanese netsuke button, an Arawak headdress and a handkerchief soaked in the blood of Charles I could be found nestling beside a stuffed alligator or a bezoar stone, calculus from an animal’s stomach held to possess magical curative powers.