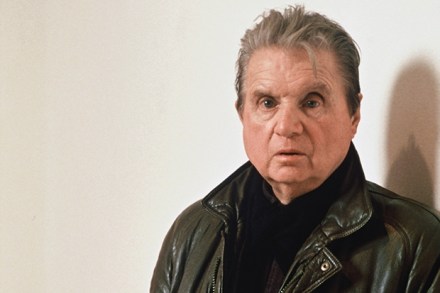

The bitterness of Bacon

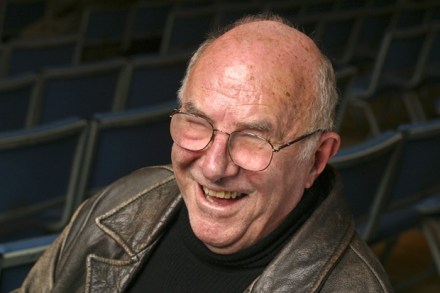

When Michael Peppiatt met Francis Bacon in 1963 to interview him for a student magazine, the artist was already well-established, and perhaps even establishment. He had been the subject of retrospectives at the Tate and the Guggenheim, and the Marlborough Gallery had paid off several decades’ worth of gambling debts. No longer an authentically marginal figure, ‘mythologising his life’ was ‘at the very centre of his existence and painting’; and for 29 years Peppiatt became his scribe, drinking partner, estate agent, confidante, gatekeeper and admirer, and the recipient of lavish dinners, drinks, flats, paintings and acquaintances. Alienated from his own family, Peppiatt grew up in Bacon’s world and only belatedly