The continent in crisis

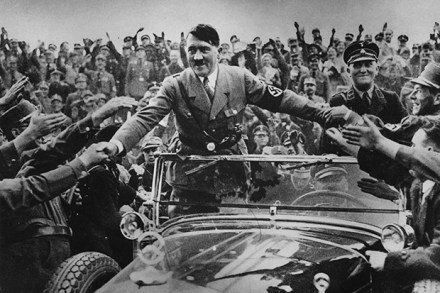

Sir Ian Kershaw won his knight’s spurs as a historian with his much acclaimed two-volume biography of Hitler, Hubris and Nemesis. He is now attempting to repeat the feat with a two-volume history of modern Europe, of which this is the opening shot.Inevitably, the figure of the Führer once again marches across Kershaw’s pages as they chronicle the years dominated by Germany’s malign master. First the Great War that gave Hitler his chance to escape obscurity, and then the greater one he launched himself. Opening with the continent’s catastrophic slide into generalised conflict in 1914, Kershaw apportions blame or the disaster more or less equally to all the combatant nations.