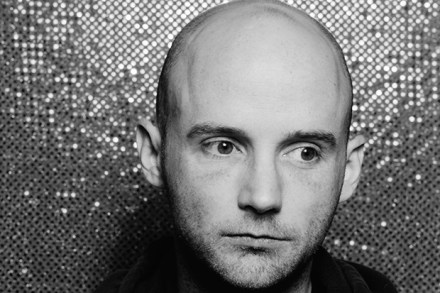

The clean and the unclean

In 1991, Moby folded the theme from Twin Peaks into a remix of his dance track ‘Go’ and a diminutive, teetotal, vegan Christian abruptly became the American rave scene’s first pop star. He was not the obvious candidate: one critic dubbed him ‘techno’s crazed youth minister’. As a showboating entertainer in a culture sceptical of stardom, and a somewhat sanctimonious puritan surrounded by hedonists, he put a lot of noses out of joint. On one early online rave forum the phrase ‘Go away Moby’ became a mantra. In his first memoir, Richard Melville Hall (nicknamed Moby due to his famous ancestor Herman) unpicks this paradox with an unusual degree of