Perfect, gentle Knight

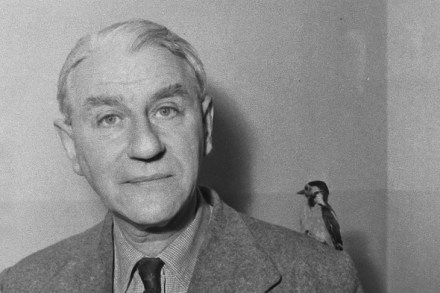

I once asked Baroness Manningham-Buller, the former head of MI5, what she did to relax. Nailing me to the wall with her no-nonsense look, she said: ‘I keep sheep.’ A similar association with the animal kingdom resounds through Henry Hemming’s excellent new life of Maxwell Knight, the famous spymaster and possible archetype for Ian Fleming’s ‘M’. Knight’s family and friends observed that, at an early age, he had a particular way with animals that allowed him to bring them under his spell. As a young man he kept a menagerie in his small London flat consisting of a bulldog, a bear and a baboon. Following his retirement, he dedicated himself