Morality tales

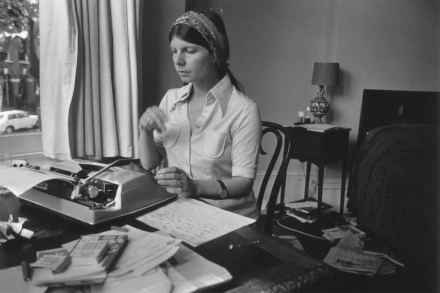

Francis King celebrates Margaret Drabble’s distinguished career and vividly recalls their first meeting I first met a youthful Margaret Drabble when, already myself an established author, I was working at Weidenfeld and Nicolson as a literary adviser. The editorial director was an Australian woman called Barley Allison, sister of an MP, who constantly boasted of having ‘grabbed’ (her word) yet another new author for her distinguished list. Her latest ‘grab’ was a sometimes pensively grave and sometimes energetically argumentative woman, an admired actress when up at Cambridge, with the totally unsuitable surname Drabble. ‘You must meet her,’ Allison told me. ‘Quite remarkable.’ When the three of us sat down to