The self-serving delusions of the ‘Swastika Kaiser’

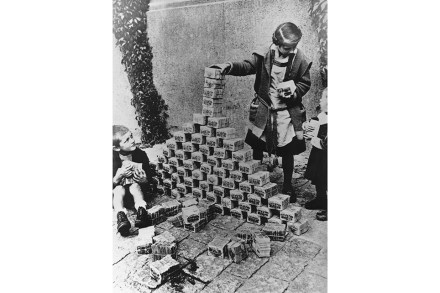

Whenever a new study of the Nazi regime appears, it is taken as a given that after Adolf Hitler seized power and became dictator of Germany in 1933 an egalitarian society emerged, very different to previous decadent, backward-looking generations. In this modern era, it is assumed, the concerns of the Kaiser and the German elite were at best ignored and at worst made another target of the Führer’s purges. In 1933, Wilhelm called Hitler a ‘torchbearer with unparalleled force of conviction and self-sacrifice’ It’s a tempting summation, but an over-simplistic one. As a biographer of the Duke of Windsor, I drew on documents that suggested that Hitler was in fact