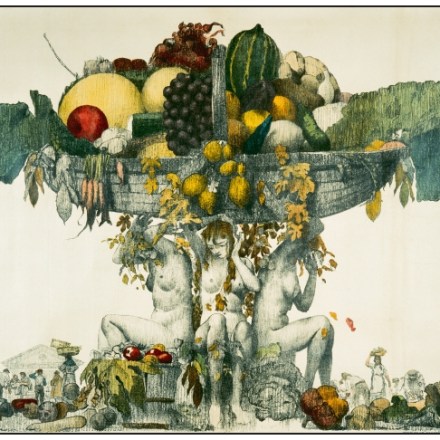

The fruits of imperialism

Imagine yourself a middle-class person in England in the 1870s. You sit down to drink a cup of tea while reading The Spectator. It probably doesn’t cross your mind, but in your hand you hold products from around the world. Your tea is from Ceylon, the sugar in it from Jamaica, and your porcelain cup