Spellbinding performance of a career-defining record: Corinne Rae Bailey, at Ladbroke Hall, reviewed

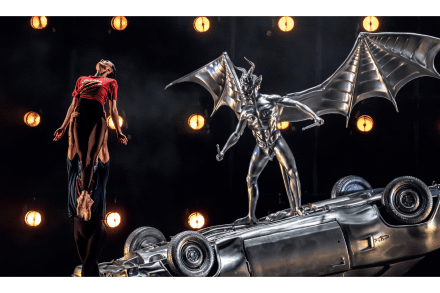

You won’t see two more contrasting shows this year than Corinne Bailey Rae performing her album Black Rainbows and Brian Eno presenting work with a symphony orchestra. One had music that did everything; one had music that did very little. But both were overwhelming and filled with joy of rather different kinds. When Bailey Rae last made an album, in 2016, it was gentle, tasteful, soulful R&B, the kind the young professional couple in a prestige Netflix drama listen to before their lives are overturned by a vengeful nanny. Black Rainbows,by contrast, from earlier this year, was an abrupt embrace of everything: from scuzzy garage punk to psychedelic soul to